Article: Mukaji: A Pendant Born from the Resilience of Congolese Women

Mukaji: A Pendant Born from the Resilience of Congolese Women

In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), being a woman means carrying an immense burden through unimaginable hardships. For decades, conflict has ravaged the country – especially the eastern provinces, subjecting countless women to brutal sexual violence and terror. Rebels have used rape as a deliberate weapon of war, shattering families and communities through cruelty. The scale of this horror defies belief: at one point a study found 48 women were raped every hour in the DRC. This staggering prevalence led the United Nations to dub Congo the “rape capital of the world,”and commentators to call it “the worst place on Earth to be a woman.” The toll of Congo’s wars has indeed been horrific, over 6 million lives have been lost in conflict since the 1990s, and millions more driven from their homes. Women have often borne the worst of this violence: mass rapes, torture, and the trauma of seeing their husbands, children, or relatives killed in front of them. Many have had to flee their villages and cities with nothing, seeking safety in camps or foreign countries as war refugees.

The Harsh Realities Facing Congolese Women

War and Sexual Violence: Years of armed conflict in the DRC have created a pervasive culture of violence against women. Rape has been widely used as a tactic to terrorize civilians and assert control. Entire villages have been attacked by militia groups who gang-rape women of all ages, even young girls and babies, as a means to destroy the social fabric. In some of the worst-hit eastern provinces, over 12% of all women have been raped at least once according to surveys. The impact ripples far beyond the individual survivor – husbands often abandon wives who were raped due to stigma, and communities are traumatized and destabilized. Even in recent years, as conflict continues, displaced women remain extremely vulnerable. In camps near Goma, on average **70 women and girls ** per day were coming forward for treatment after sexual assaults in 2023. In a single month (July 2023), Doctors Without Borders treated 1,500 female rape survivors in just three camps around Goma, double the number from two months earlier. These numbers underscore how Congolese women and girls continue to pay a devastating price in what has rightly been called “a war against women”.

Displacement and Loss: The conflicts have uprooted families on a massive scale. As of 2023, a record 6.9 million people are internally displaced inside DRC, one of the largest displacement crises in the world. Over 5 million of these displaced are in the conflict-torn eastern regions, and the majority are believed to be women and children. In 2022 alone, more than 4 million people fled their homes due to fighting, the highest figure in Africa. Refugee camps and displacement sites are filled with mothers and young girls who have lost everything. Of nearly 100,000 people who arrived to camps near Goma in mid-2023, about 60% were women and girls. Many are widows or single mothers who saw their husbands killed or missing in the war. Others were separated from family in the chaos of fleeing. Besides the threat of sexual assault in these camps, displaced women face dire struggles to feed their children, find water, and maintain dignity in extremely harsh conditions. Across the wider region, over one million Congolese women have been driven into exile in neighboring countries and beyond, forming a far-flung diaspora. Nearly half of these refugees are in Uganda, with large communities also in Rwanda, Tanzania, Burundi, and Western countries. Every refugee carries with her the trauma of what she endured in Congo – yet also the hope of rebuilding life in safety.

Everyday Oppression and Strength: For those Congolese women not directly caught in war, life is still marked by deep-rooted gender inequality and struggle. In Congolese society, women’s roles are traditionally viewed as subordinate, they are expected to cook, clean, farm, bear and raise children, yet often receive little respect or voice. Patriarchal customs and laws have long treated women essentially as minors under the authority of fathers or husbands. Until 2016, the Congolese Family Code even legally required a married woman to obey her husband and barred her from working without his permission (these provisions were finally revised, but attitudes change slowly). The result is a pervasive belittling of women’s mental and physical capacities, a notion that women are less capable than men outside the home, which continues to limit women’s opportunities in education, work, and leadership.

Yet, the reality is the opposite: Congolese women carry entire families on their backs, often literally and figuratively sustaining the nation. They farm the fields, run small businesses in the markets, and raise the next generation – all while enduring society’s dismissal of their worth. Consider some telling facts:

-

Primary Providers: In the DRC’s largely agrarian economy, women are the main food producers for their households. Their contribution to farming and production is nearly equal to men’s; women till the land, plant and harvest crops, and ensure their families are fed. This is true even in “male-headed” households, not only single-mother families. However, this hard work remains undervalued and unpaid, as men typically control any cash crop income or land ownership rights. Customary law in many communities denies women the right to own or inherit land, despite their central role in cultivating it.

-

Heavy Workload: Women shoulder a double burden of productive labor and domestic duties. On top of farming or trading, a Congolese woman is expected to cook, clean, fetch water and firewood, bear children, and care for the extended family. This “dual role” leads to extremely long days and exhaustion, with women having very little time for rest or personal advancement. It is not uncommon to see Congolese women carrying firewood or produce on their backs, a baby strapped to their front, while balancing a basin on their head – a potent image of strength and responsibility.

-

Lack of Voice and Power: In both family and public life, women have historically had limited decision-making power. Men are often considered the head of the household whose word is final. Surveys show women in DRC often have little control over household decisions like finances or major purchases. In fact, many husbands believe they have the right to confiscate or misuse their wives’ earnings, undermining women’s economic independence. In one study from Goma, 80% of women entrepreneurs said their husbands actively hindered their businesses, some stealing their wives’ money or sabotaging their work out of a need to assert dominance. Politically, women are similarly underrepresented. After the 2018 elections, only 10.3% of national assembly members were women, one of the lowest rates in Africa. Women’s voices are too often absent from the very parliaments and councils deciding the country’s future. This lack of representation perpetuates laws and institutions that fail to protect women’s rights.

-

Barriers to Education: Traditional attitudes that “a girl’s place is in the home” have meant that many Congolese girls receive less education than boys. Families struggling with school fees often prioritize sons, while daughters may be kept home to help with chores. As a result, female literacy lags behind, as of 2012 only about 63% of young women were literate, compared to 88% of young men. Though this gap has narrowed in recent years with government and NGO efforts, girls still face higher dropout rates due to early marriage, teen pregnancy, or simply the expectation that a woman doesn’t need much schooling. This denial of education is essentially a belittlement of women’s intellectual potential. It has long-term effects: without qualifications, women remain shut out of formal employment and leadership positions. In fact, only 6.4% of Congolese women work in paid wage jobs (the rest work informally or unpaid at home), a shockingly low figure next to 23.9% of men in wage employment. The vast majority of women make their living through informal petty trade, subsistence farming, or family labor – vital contributions, yet ones that come with low status and income.

-

Violence and Impunity: Beyond the conflict-related violence, Congolese women also face high levels of domestic and sexual abuse in everyday life. Cultural norms of male dominance, coupled with weak law enforcement, mean many women suffer beatings or marital rape behind closed doors. Domestic violence is widespread, one study found reported incidents of wife abuse rose 17-fold between 2004 and 2008. Unfortunately, impunity is common; families often prefer to “solve” rape cases by accepting a dowry or payment from the perpetrator’s family rather than prosecuting. This leaves survivors without justice. Overall, observers note that violence against women in DRC is “a national trend” sustained by weak legal protections. The trauma from such abuse, on top of economic hardship, forms a daily reality for many women. And yet, these same women continue to toil for their families and persevere.

In sum, whether facing the extraordinary horrors of war or the ordinary injustices of patriarchy, Congolese women have endured suffering that is difficult to fathom. They have seen their bodies used as battlefields, their rights stripped away, and their contributions dismissed. But this is far from the whole story. Equally important is how women have responded, with quiet resilience, strength, and love that hold their communities together even in the darkest times.

Unsung Heroines: The Strength of Congolese Women

Every Congolese woman, whether in a remote village, a bustling city, or the diaspora abroad, carries within her the legacy of generations of resilience. These women are often the unsung heroines of Congolese society. In the face of war, it is women who pick up the pieces of shattered households, caring for orphans, nursing the wounded, planting new crops in burned fields. In periods of relative peace, it is women who sustain daily life through their labor and ingenuity, despite the odds stacked against them. For example, when men go off to fight or mines, women step into traditionally male roles: they trade, farm cash crops, and manage finances to keep the family afloat. Years of conflict have in fact forced social shifts, the number of female-headed households has risen sharply, meaning more women must act as sole providers and decision-makers out of necessity. Although this brings added burdens, it also shows women’s remarkable capacity to adapt and lead when circumstances demand it.

The Congolese culture itself, beneath the patriarchal surface, holds deep respect for the concept of the mother and the strong woman. In many local traditions, women are seen as the backbone of the family and “mothers of the nation.” There is even a popular saying that “women hold up half the sky.” Time and again, Congolese women have exemplified courage: women activists bravely speak out for peace and justice, market women form associations to support each other’s businesses, mothers teach their children values of tolerance and hard work, and survivors of violence form networks to heal and help fellow women. Their strength doesn’t need to be loud to be remembered. As one observer noted, Congolese women “carry generations of resilience in silence and grace”, their power often expressed through steady perseverance rather than words. They are quiet rebels who, simply by refusing to give up, push back against a society that undervalues them.

This immense fortitude is not lost on those who have witnessed it. Many in the Congolese diaspora, women who immigrated to Europe, North America, or elsewhere, draw inspiration from the endurance of their mothers and grandmothers back home. Diaspora Congolese women often juggle working multiple jobs in a new country while sending money to support relatives in the DRC. They become cultural ambassadors, showcasing Congolese fashion, music, and entrepreneurship globally, all the while retaining a fierce pride in their identity as “Mukaji”, women of Congo. Whether at home or abroad, Congolese women share a bond of resilience. They have suffered, yet they continue to rise. It is this reality, brutal yet hopeful – that inspired the creation of the Mukaji Pendant.

Mukaji: A Symbol of Honor and Hope

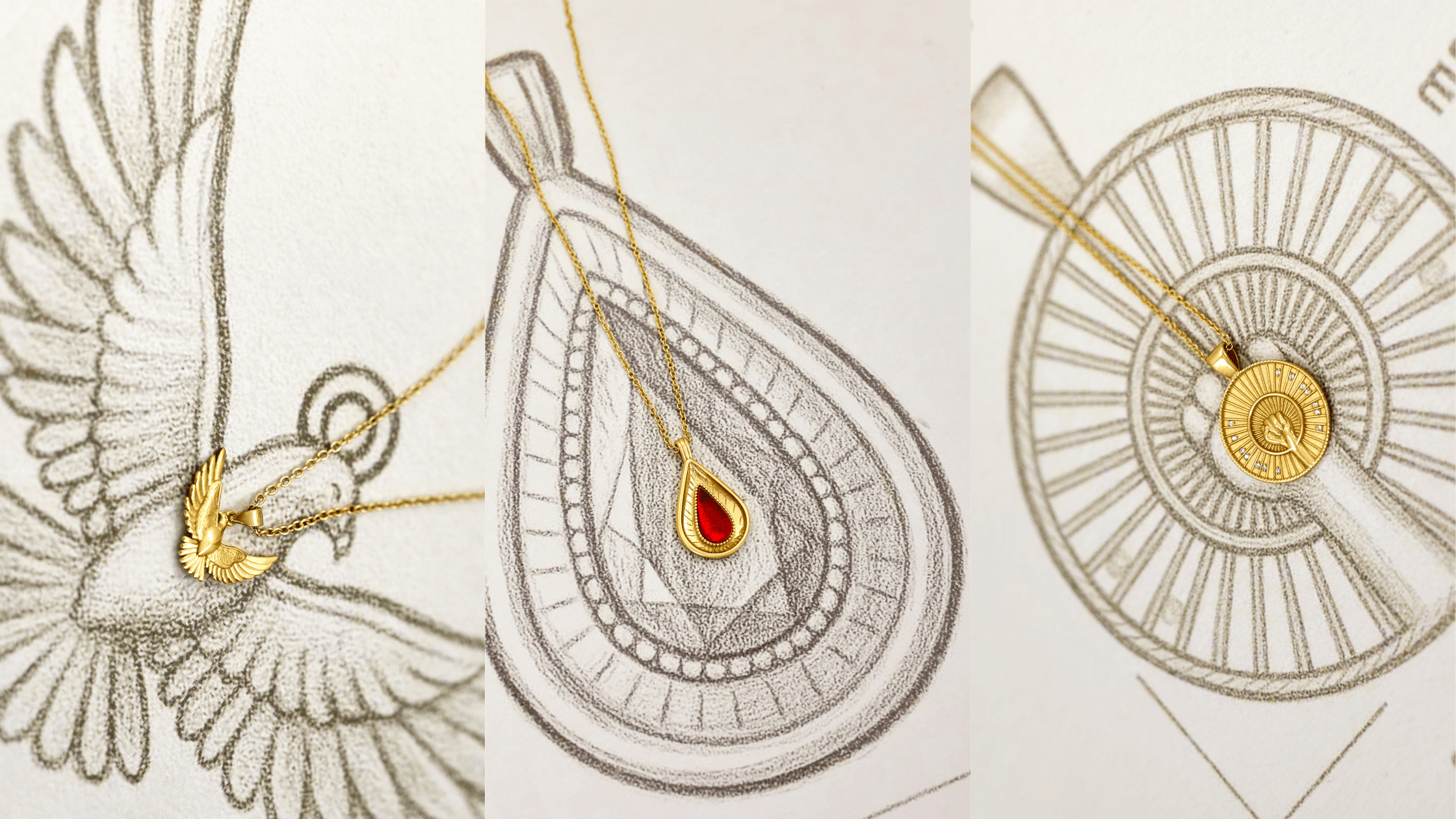

The Mukaji Pendant by Maison DORAMS features a raised fist framed by a radiant sunburst. Crafted in gold, it is a wearable tribute to the strength, grace, and quiet power of Congolese women.

The Mukaji Pendant was born from a desire to honor Congolese women and shine light on their stories. Its very name carries profound meaning: “Mukaji” means “woman” in one of the languages of the Congo (a term of respect in the designer’s own culture). This piece of jewelry was envisioned as more than an accessory, it is intended as a sculptural tribute to the Congolese woman, capturing both her suffering and her hope. The pendant’s creator, Doriane Kanguvu, is a Congolese woman who grew up “surrounded by powerful women, grandmothers, mothers, sisters, who carried generations of resilience in silence and grace.” These women’s quiet strength deeply influenced her. Doriane founded Maison DORAMS with a mission to tell stories through jewelry, and the Mukaji Pendant is the heart of that mission. It was designed “for the woman who refuses to be defined by the world, the woman who chooses to define herself,”as the brand’s philosophy states. In essence, Mukaji is a celebration of feminine resilience and African heritage, distilled into a wearable form.

Every element of the Mukaji Pendant’s design carries symbolism tied to Congolese women’s reality:

-

The raised fist at the center of the pendant is a universal emblem of strength, resistance, and solidarity. Here it represents the quiet triumph of Congolese women; their refusal to be broken by adversity. The fist is uplifted but small and delicate, conveying how these women’s courage is often unassuming yet unyielding. It echoes the fists of women who have marched for their rights or simply persevered through pain, silently saying “we are still here.” By wearing this symbol close to the heart, one honors the fight and dignity of all our “mukaji”, our mothers, sisters, aunts, and daughters of Congo.

-

Radiant sunburst rays emanate from behind the fist, forming a halo-like frame. This motif of rays or a rising sun evokes hope, rebirth, and a new dawn. For the women of Congo, it signifies that even after the darkest night of violence or oppression, there is hope of sunrise. Each ray can be seen as a prayer for unity and healing in their communities. The sunburst also nods to the idea of women as sources of light in their families, much as a sun brings warmth and life. The 14 points of the sunburst are not arbitrary: they are adorned with fourteen sparkling stones, each one representing the inherent preciousness of Congolese women. Notably, Congo is famed for its mineral wealth (gold, diamonds, coltan) – riches for which it has also suffered conflict. The pendant deliberately uses gems to symbolize Congo’s diamond legacy. In some versions, genuine conflict-free diamonds are used, transforming symbols of past exploitation into icons of hope. Each gem “twinkling in the sunburst is a reminder of completion, unity, and hope,” according to the designer’s description. Just as many stones come together to form the circular halo, the many roles and contributions of women together complete the picture of a thriving society.

-

The materials themselves carry meaning. The Mukaji Pendant is available in solid 18k gold or gold vermeil (gold-plated sterling silver). Gold was chosen for its enduring, untarnishing nature – “a metal that endures as endlessly as the legacy it represents.” Gold’s warmth and glow reflect the inner light of the women being honored. Importantly, the gold and stones are ethically sourced from conflict-free suppliers, ensuring that the tribute to Congolese women is not tainted by the very injustices that have harmed them (such as conflict minerals). Each pendant is crafted by artisans with great care, as if creating a piece of living heritage. The result is not just a mass-produced trinket, but a meaningful emblem meant to last for generations; much like the stories of the women it symbolizes.

Wearing the Mukaji Pendant is meant to be a statement of solidarity and pride. It allows those who wear it – whether they are Congolese or simply moved by the cause to literally wear their heart on their chest. When someone compliments the necklace, it opens the door to share its story: “Mukaji means ‘woman’ in my culture’s language, and this piece honors the strength of women.” In that simple explanation, awareness is raised and the legacy of Congo’s women is kept alive. Each time the pendant catches the light, one can be reminded of the resilience of a grandmother who survived war, or the grace of a mother who toils without thanks. The pendant thus becomes a conversation between the wearer and her heritage, a quiet rebellion and a shining badge of courage.

The origin of the Mukaji Pendant lies in both heartbreak and hope: the heartbreak of knowing what Congolese women have endured, and the hope of celebrating their indomitable spirit. Doriane Kanguvu designed it so that “every curve and every facet carries a story”, the clenched fist for courage, the sunburst for hope, the circle for unity. It is jewelry with a soul. By creating this pendant, she sought to ensure that the suffering of her “sisters, mothers, aunts” in the Congo is not forgotten, and that their quiet heroism is recognized and honored in the wider world.

A Living Legacy

The Mukaji Pendant now lives as a small piece of wearable art, but its significance comes from the very real lives it represents. It stands as a testament to all Congolese women, whether in the villages of North Kivu or the diaspora communities of Europe and America. When you hold it in your hand, you feel the weight of story and sacrifice far beyond its material value. It is a reminder of the horrors that must never be repeated. The rapes, the killings, the injustice, but also a reminder of the hope that must never die, the hope embodied by every woman who gets up in the morning and cares for her family despite the difficulties.

Ultimately, the Mukaji Pendant is about turning pain into purpose and tragedy into triumph. It invites us to reflect on the reality of Congolese women’s lives and to celebrate their resilience. In wearing it, one symbolically shares a bit in their burden and also in their strength. As the Maison DORAMS mantra goes, this is “Luxury with Meaning”, a luxury that does not exist for its own sake, but to carry a legacy. The legacy of the Mukaji is the legacy of all Congolese women: of suffering bravely borne, of contributions too often overlooked, and of strength that shines quietly, like a diamond in the dark.

By shedding light on their reality through factual truths and heartfelt design – we honor these women. The Mukaji Pendant is a small, golden light dedicated to them. And in that light, we see not victims, but victors: the proud, unbreakable spirit of Congolese women, past, present, and future, captured in a symbol that will endure.

Sources:

-

Adetunji, Jo. “Forty-eight women raped every hour in Congo, study finds.” The Guardian, 12 May 2011.

-

Murdock, Heather. “Domestic Rape in Congo a Rapidly Growing Problem.” Voice of America, 29 May 2011.

-

Associated Press. “'I Wanted to Scream': Conflict in Congo Drives Sexual Assault of Displaced Women.” AP News(via VOA), 29 Oct 2023.

-

Agence France-Presse. “UN: Record 6.9 Million Internally Displaced in DR Congo.” AFP (via VOA), 30 Oct 2023.

-

Panzi Foundation. “War in Congo” – Crisis Overview.

-

Rainforest UK Report. Gender Inequalities, Access to Land and Community Forestry in DRC, 2021.

-

World Bank Blogs – Donald et al. “Obstacles and opportunities for women’s economic empowerment in DRC.” World Bank, 2 June 2022.

-

Maison DORAMS – Mukaji Pendant Description and Brand Story.

Laisser un commentaire

Ce site est protégé par hCaptcha, et la Politique de confidentialité et les Conditions de service de hCaptcha s’appliquent.